Residents, tourists, taxi drivers, or just in town for a business meeting, Google Maps or Waze might tell you what the fastest route is, but is it also the safest? And if you fall victim to street violence, can you connect to the police in one click?

To find out, we spoke with Base Operations, a social startup that lets you navigate through a ‘security heat map’ of six Latin American cities, about the potentials and challenges of improving street safety in the digital age.

Cory Siskind spent several years navigating her way through Mexico City, a typical Latin American urban ensemble of ever-changing ‘safe’ and ‘unsafe’, of streets to cross and those to avoid. However, she became increasingly frustrated with the simple lack of information: Security advice seemed limited to expensive on-demand services for private companies and ignored the opportunities of data harnessing in the digital age.

The 10 most dangerous cities of the world are located in Latin America. Poverty, gang violence, drugs and corruption have led to a proliferation of street crime in many cities. While the probability to become victim to serious assaults or even homicides is relatively low, it still creates a toxic atmosphere of insecurity and anxiety among its residents and visitors whenever entering less-known neighborhoods.

“So much brain power goes into solving problems like ‘getting people the exact Amazon product.’

Why can’t we can use those same technologies to solve larger social problems – like chronic violence and insecurity?”

In response, Cory Siskind and her business partner Nick Gomez founded Base Operations. By mining through different sources including police reports and crowdsourced data, the app creates ‘crime heat maps’ that are used to suggest safe navigation alongside security analysis and advice. The service will be launched in six cities of Latin America, including Mexico City, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Santiago, Montevideo and Buenos Aires.

And while the app is just in beta phase, the team have already managed to assemble some big names behind them. The startup is backed by several MIT bodies such as the Legatum Center for Development and Entrepreneurship, has recently been part of Techstars’ new social accelerator program, and is currently piloting its product with global consulting firm Bain & Company.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QlSoxl9lS9Q

Digital technologies are hailed to provide solutions for social issues from education to healthcare, yet personal security is a field that has traditionally been much more tech-resistant. Public authorities, the army and police might be heavily investing in technologies related to big data, AI or IoT – but for the average citizen, tourist or taxi driver, security information is still overwhelmingly limited to word-of-mouth.

Entrepreneurs like Siskind and Gomez want to see a change. “So much brain power goes into solving problems like getting people the exact Amazon product that they need. But why can’t we can use those same technologies and advancements to solve larger social problems – like chronic violence and insecurity?” they asked us.

Cory Siskind, Co-founder of Base Operations.

Base Operations is not the only advocate of making more data available to the public. For example, Igarapé Institute in Rio de Janeiro created a crime map of the city called CrimeRadar, using past data on reported crime that was previously not available online.

In El Salvador, newly launched Smart912 is equally setting out to become the next ‘Waze for crime‘ that proposes the citizens-protect-citizen principle by allowing security alerts to be publicly sent to those nearby. In the first week of launching, the app reported 4000 downloads, and seems to be gaining increasing attention.

Other apps are trying to make reporting of crimes easier: For example, the app Seguridad Provincia was created by the Argentinian government to allow citizens to report crimes like robberies online – but also to eliminate the corruption of some police officials. “From now on, the police inspector does not have the total control over crime reports anymore,” said Buenos Aires Governor María Eugenia Vidal in a public statement when the app was launched in 2017.

Vive Segura is an app backed by the Mexican Government that allows victims to report incidents of sexual violence online, to be followed up by the judicial system as well to generate a better picture of affected city areas. Two-thirds of Mexican women have been victims to gender-based violence and many fall victim to harassment and violence outside of their home; on public transport, for example.

While apps like these are being launched all over Latin America, digital solutions to improve personal security is still a relatively immature sector that is just emerging. What has held the industry back for so long, and what can be learned from the initiatives to date?

1. The Data Challenge

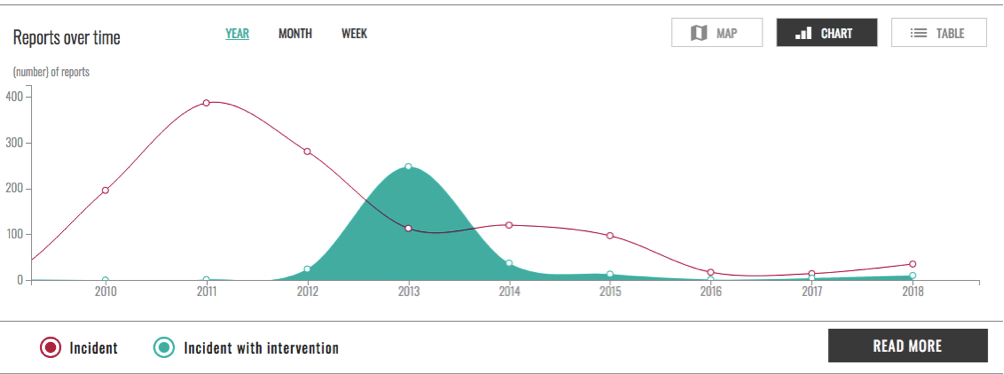

Many applications are trying to crowdsource their data, but getting to a significant scale of user traction can prove extremely difficult. Taking an international example, HarrassMap from Egypt was one of the first online tools for women to report incidents of public harassment. These voluntary entries are visualized in maps of affected areas. While the initiative certainly reached its goal to create awareness and reports initially peaked, the usage seems to be phasing out.

Applications that rely on several data sources might have it easier. For example, Base Operations is not only crowd-sourcing, but also harnessing data from public authorities, partner companies as well as data-mining social media.

Lesson learned from HarrassMap.org: Crowdsourced data may be hard to sustain. Image: https://harassmap.org/

2. Trust is central

In a setting where misinformation can have serious consequences, users need to trust that security alerts are always up to date. CrimeRadar has created good visualization of past incidents, but how much trust will users put on a pre-crime map that is forecasted from this past data?

Similarly, requesting users to disclose sensitive personal information, such as reporting online incidents of sexual violence, requires a stable amount of trust that privacy rights will be respected, as well as steps for a follow-up taken by authorities.

The sluggish usage of Mexico’s online reporting tool Vive Segura may be linked to the well-known problem of judicial impunity when it comes to gender violence. Similarly, many users on the Android store site of Seguridad Provincia from Argentina complain that it is not possible to file reports anonymously, even though there are cases where they feel endangered by giving out all their personal data.

3. Find the truth in between the noise

“We need to find the truth in between all the noise,” is how Cody Siskind summarises the startup’s core mission. Reports on security incidents are often conflicting and highly biased. Good security advice does not mean to paralyze users by swamping them with a large quantity of data. It also means verifying and filtering out the important information, providing a sensible analysis and making the information actionable. For example, by suggesting different routes to take through the city, or directing users to report crime to the local police with one click.

Personal security has been a field that has been slow to catch up with digital technology. However, new applications are giving hope to make the troubled streets of Latin American major cities safer. “Violence is a complex problem, and we can’t solve everything. But we want to tackle one part, which is access to information and transparency,” say Siskind and Gomez.

With staggering crime rates from Ciudad de Mexico to Rio de Janeiro, anybody navigating these streets should be hoping that more entrepreneurs will follow their mission.