This article was first published on Latin America Reports.

Sex education is a tricky topic all over the world. When is too early to teach it? When is too late? But, in Latin America, throw in a hefty dose of conservatism and a pervasive Catholic culture and you’ve found yourself an explosive mixture.

Argentina passed a law in 2006 that proposed a country-wide comprehensive sexual education curriculum (ESI), that would include teaching children about contraception and promote non-discrimination against LGBT individuals. Thirteen years later it is sporadically being implemented and to varying degrees across provinces and in schools. Last year a follow-up commission was created to bring the ESI into the public eye again, and by highlighting the importance of valuing sexual diversity and addressing the term “gender” in addition to biological sex, they certainly succeeded, but unlikely in the way they intended.

Why has the new ESI proposal been met with so much resistance?

It is the “gender ideology” component that many people are rejecting. This means separating and valuing a person’s “gender” (a social role based on an individual’s self-identity) in addition to their “sex” (the anatomy that determines whether you are biologically male or female).

The Argentine anti-gender ideology movement #ConMisHijosNoTeMetas (Don’t mess with my kids) states on their Facebook page that the term gender “applies to a focus that interprets the human according to invented concepts, with neither scientific backing or foundation. It wants to take the place of and denaturalise the human reality.”

The law’s objective to “value diversity” has also been interpreted as a promotion of homosexuality and an attempt to break down the traditional family structure. Many also believe that too much content is being taught at a very young age.

“We worry that it will eroticise our children systematically, and too early,” Mónica del Río, head of the Federal Family Network, told Latin America Reports. “We reject the ESI that is trying to impose itself in a totalitarian way, because we want to educate for love, for marriage, and for family.”

Is ESI resistance fueled by traditional views and Catholic heritage?

The Spanish colonists justified their claims to the New World based on a Christianizing mission, explained Latin American professor John F. Schwaller in the book “The Church in Colonial Latin America,” adding that people were born, lived and died under Church control. Despite the fact that adherents to Catholicism are declining in the region (from 98% in the 1970’s to just 59% currently), a Pew Research report suggests that this reduction could be attributed to a movement from Catholicism to other branches of the Christian faith such as Protestantism or Anglicanism.

Nevertheless, this still means that the majority of Argentine society were raised in Catholic households, and it could be these ingrained beliefs that have affected the implementation of the ESI.

Some of the more orthodox adherents to the Catholic faith follow Pope Paul VI’s 1968 text “Humanae Vitae,” which condemns the use of “artificial” contraception in any circumstances. This was met with widespread international rejection, and seemed to have little effect, as a 2015 UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs study reported that 72.7% of Latin Americans use contraception, a 36.9% increase since 1970.

However, there are still those who agree with Pope Paul VI’s attitude and believe that artificial contraceptives could have a harmful effect on society. Renzo Paccini, a Bioethics doctor at the University of San Pablo addressed this in his essay “Gender Ideology in Latin America.”

“If we keep in mind that the use of contraceptive methods are “heraldic” of abortion – both being expressions of the same anti-conception mentality – it is to be expected that the Latin American public will become more permissible in respect to abortive practices and its subsequent legalisation,” he wrote.

Federal Family Network leader Del Rio agreed that there were downsides to relying on contraception.

“The strategies in the ESI designed to reduce unwanted pregnancies and avoid the spread of sexually transmitted diseases have failed,” Del Río said. “It has been reduced to the use of contraception, which only slightly lowers the risks that trivialising sexuality has exponentially increased.”

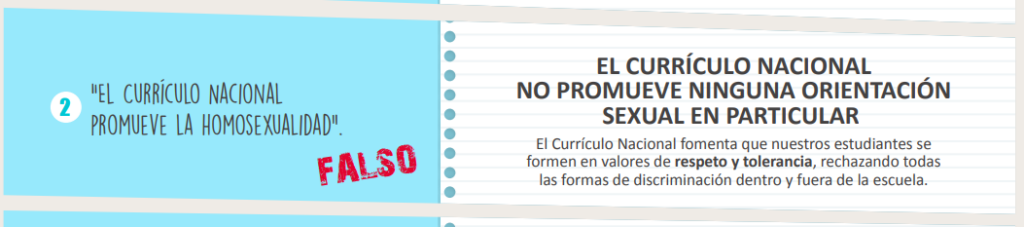

The ESI’s non-discriminatory policy towards LGBT individuals has led many to believe that their children are more likely to become gay. This even led to the Peruvian Ministry of Education – who have a similar gender ideology focus in their proposed sexual education curriculum – to release an “myth debunking” infographic explicitly stating that the curriculum does not promote homosexuality.

The focus that men and women are inherently equal is a leading element of the ESI, but this has also been faced with opposition as it can be seen as stripping women of their inherent role, “‘de-constructing’ family, marriage, maternity and femininity itself,” explained Paccini. “[…] It doesn’t therefore uphold women’s interests, as should be expected from any kind of ‘feminism.’”

“South American women want to have children,” explained Neldy Mendoza de Chavez, spokesperson for Peruvian pro-life group CORVIDA at a march last year. “They want to take care of them, watch them grow, accompany them in their childhood and adolescence and enjoy, ultimately, their family life.”

“But social pressure leads them to hide their motherhood, to delay it, to conceal their maternal calling and it causes them to show that children prevent them from being ‘equal to men.’”

This “social pressure” is coming from the recent wave of feminist movements in both Peru and Argentina, such as #NiUnaMenos (against femicide), #MiraComoNosPonemos (against sexual abuse) and the fight for free, legal and safe abortion – all movements that have been represented by the symbolic green handkerchief.

It’s not all about the Bible

However, these radical views are not necessarily those shared by the majority, Martín Vergara, graduate of Educational Science, explained. What many people reject is the fact that the gender ideology would be taught from one viewpoint only, without taking into account the diverse and multicultural nature of Argentina’s society.

“We live in a democratic country, super diverse, with many beliefs and many cultures,” he told us. “The law should reflect that. I don’t think it’s democratically healthy that the ESI is taught from just one point of view. I can explain how I think a family should be, but I don’t have the right to impose that on anyone else.”

He quoted article 12 of the American Convention of Human Rights, stating that individuals have the right to “conserve their own religion and beliefs,” something that he believes the ESI is endangering.

This raises the issue of who has the right to educate their children: the parents or the state? Although Vergara and Del Río both agreed that the parents are the primary educators, Del Rio feels that parents should remain so during the child’s upbringing.

“The 2006 law ignores the parent’s right/duty to educate their children, something that, as well as being natural and primary, in Argentina is recognised by various laws in the constitutional hierarchy,” she said. “The state – in this area – has merely a subsidiary function.”

Vergara disagrees, however, stating that education should be a mix between parents and educational establishments.

“Often, parents mistreat their children,” he said. “They don’t look after them, they don’t guarantee their rights or they rape them. It needs to be a balance, parents must listen to the schools, but equally the schools must be prepared to listen to the parents as well.”

Why is the ESI important?

Ultimately, the ESI hopes to reduce discrimination, prevent sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancies, as well as giving young people tools to avoid sexual abuse, such as teaching about consent and what options are available to them if they do become a victim.

For Argentina, and Latin America as a whole, these are issues that need to be addressed. The region has the second highest rate of teenage pregnancy in the world, and although Argentina has lower rates than most, according to a study by the Argentine UN Population Fund (UNFPA), 300 children are born every day to teenage mothers.

A study published in Science Daily reported that “teens who received comprehensive sex education were 60 percent less likely to report becoming pregnant or impregnating someone than those who received no sex education.” Although there several studies show limited effectiveness of sexual education on teenage pregnancies, in Argentina it isn’t just uninformed teenagers causing them.

Unwanted pregnancies are often caused by sexual abuse, which is also a prominent issue in Argentina. Although it often goes unreported and there is no formal data as to exactly how many teen pregnancies are caused by abuse, a Ministry of Health report stated that “many pregnancies that occur in teenagers under 15, and in particular under 13, are product of sexual violence.”

According to a 2018 study looking at the correlations between sexual education and sexual assault, “school-based sex education promoting refusal skills before age 18 was an independent protective factor; abstinence-only instruction was not.” The ESI curriculum highlights the importance of developing communication skills and understanding consent, as “expressing feelings also constitutes a fundamental tool at the moment of preventing or reporting situations of abuse.”

“The ESI exists so that children can differentiate a caress from abuse,” explained historian Federico Sartori, whose comments became viral on social media. “The ESI is so that adults lose power over the bodies of children. So that children learn that no adult can touch them without consent, and that some caresses are not what they seem.”

“[…] Seventy percent of abuses happen in the family home. That is why comprehensive sexual education is obligatory. It doesn’t matter if you don’t want your kids to learn it. Children are subject to law, they are not the property of their parents.”

For the ESI to be more widely accepted, the government may have to make some changes. However, an effective compromise is becoming increasingly so that it can finally be implemented across the country. Beyond the debate of whether it is the state or the parents’ right to education their children, a comprehensive sexual education protects young people, but also gives them the tools to protect themselves.

Related Stories: