Ten years ago, Jorge Alderete opened a book named Easter Island and its Mysteries by Steven Chauvet, and fell headfirst into an obsession with the enigmatic island that might never end.

Easter island, or Rapanui as it’s known to the locals, is a small volcanic piece of land in the middle of the Pacific ocean, 3,686 kilometres away from the coast of Chile. It is famous for the impressive stone head sculptures (or Moais) that dot the land and whose bodies lie inexplicably buried in the volcanic earth. How did they get there? How did the communities who created them move the giant sculptures? And what were they supposed to represent? Alderete, along with countless other artists along the course of history, couldn’t get these questions out of his head.

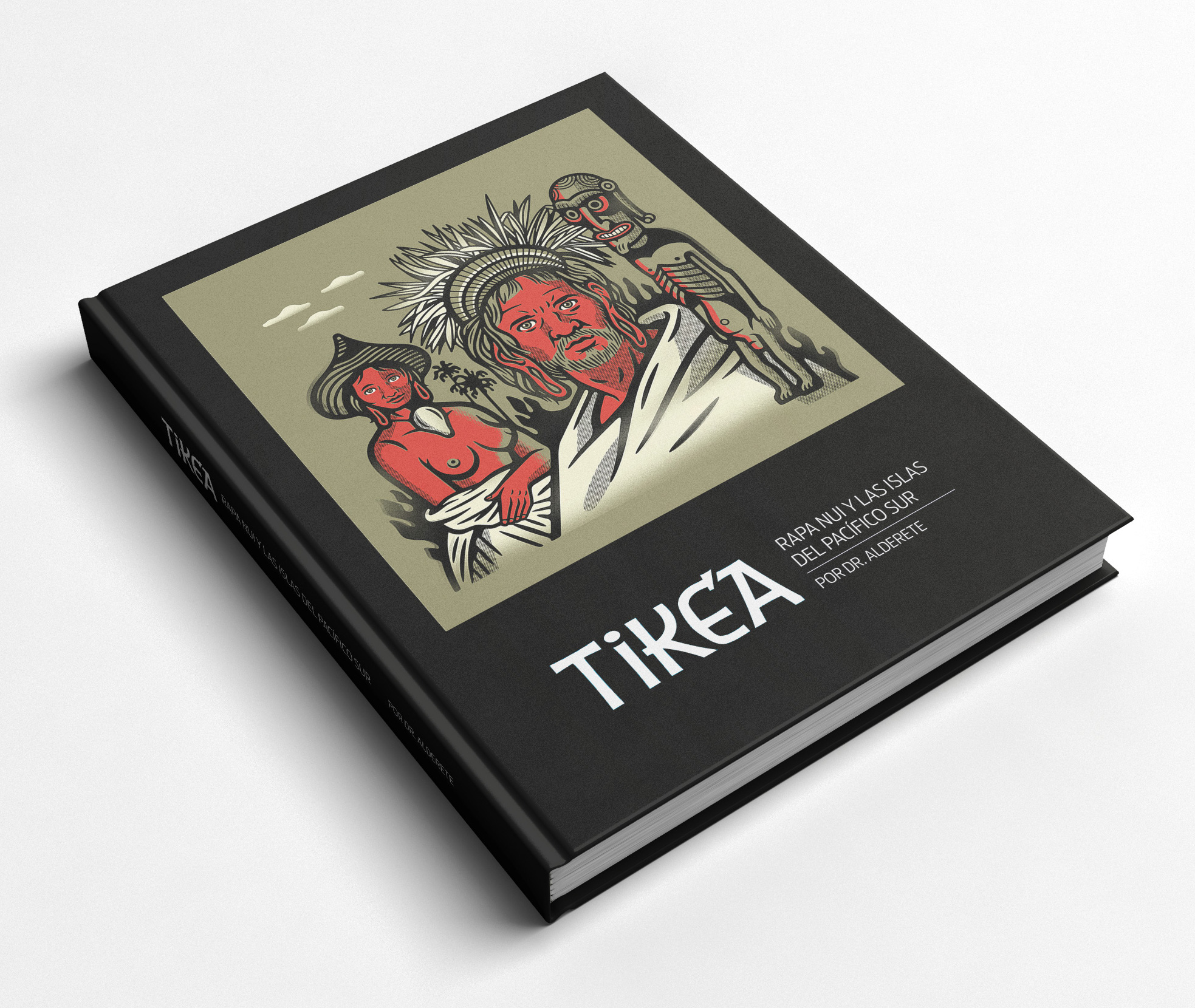

Alderete is an Argentine artist who created a body of work inspired by the island, which has been exhibited in Mexico and on Easter Island itself, and has released Tike’a, a bilingual book in English and Spanish, which compiles the results of his decade-long obsession. We spoke to the man himself at Medellin’s Book and Culture Festival which is currently taking place in the city’s botanical garden and ends on Sept. 16.

Some of the answers have been edited for brevity.

Alderete is strongly influenced by pop art, music covers and contemporary culture.

B.P. What is it about Easter Island that provokes such fascination, for you and the artists before you?

J.A. I think there are various factors. If we go back, the famous author Herman Melville wrote Typee about his experiences living in a cannibal tribe in the Pacific islands. When he wrote it, he created a new genre of literature, the South Seas genre, to which Jack London, Robert Louis Stevenson and other literary greats also added.

Throughout history, there have been various things that have added to the collective imagination that mean that today we are still marvelling at this culture. Unfortunately, Easter Island has a tragic history; slave boats ripped away large parts of the population, including their priests, their wise men, their kings and more. They also brought illnesses which decimated the population because they didn’t have the antibodies to fight them. At one point, the island had a population of only 110 people, and there were no scribes or wise men left, so much of the island’s culture and history were lost. It’s the only island in the Pacific that has its own written language, and there is an incredibly rich culture there, but so little is known about it.

For this reason, the moment people came from the West and set foot on the island, they dedicated themselves to filling in the gaps of unknown history with fantastical stories, alien civilisations and each new archaeologist had a new theory of how they moved the Moais from one end of the island to the other.

Even now there are so many things that we don’t know, that we will never know, that will stay in the terrain of the forgotten. It’s part of a history that will never be understood. So we fill the gaps with incredible stories and I think it is this that gives Easter Island in particular a mysterious aura and, for me at least, this is what enchanted me. This aura, and the fact that it is still there now, present and tangible.

Image courtesy of Dr Alderete

B.P. Do you think it would be a shame if we ever managed to understand all the mysteries that surround the island?

J.A. *Laughs* No, I don’t think I could see it as a shame, I think that new doors would open, new knowledge or new theories…it’s complicated. I don’t think I would have got so involved if these gaps didn’t exist.

In a way, my book is the story of an obsession. And it’s no coincidence that this obsession hasn’t just happened to me, you can see at the end of the book a review of all the publications and magazines from all over the world, showing how the island has gripped others. It’s no coincidence that it’s Easter Island, and not any of the other thousands of islands in Oceania that fascinated them. We are drawn to what we don’t know.

B.P. After spending years researching the island’s history, when you first visited in 2012, was it a shock to arrive and be confronted with the modern island?

J.A. I think that that was one of the things that really surprised me during the whole process. First it was an investigation that started off my own back, I did it in my free time and in breaks throughout the years. But the first time I visited the island I had the chance to confront all this knowledge I had acquired from books with what was actually there. It’s an open-air museum, the moais, the volcanos, the quarry, everything is still there, they just left it one day so you can see the whole process of how they did it.

You can confront all knowledge in some way. But I was confronted with the present and that was a surprise because it wasn’t part of my plan. Until that moment it had been time travel, a journey backwards, and now I was arriving at a society of normal people who live like anywhere else, just with a very rich and very present history.

B.P. When you presented your Tike’a exposition on the island itself, you supplemented your work with portraits of the people who currently inhabit the island. Why was this important for you?

J.A. For me it was extremely important to show the exposition for the first time on the island. It seemed fundamental, I felt indebted in some way to the island. I arrived as a complete stranger from thousands of kilometres away to show them an exhibition on their own culture. What right did I have? Thankfully it was very well received, and this last part – the portraits – really helped with that. With the historical part of my work representing the moais and the island, maybe I could interest them with a new graphic representation and aesthetic, but in reality I wasn’t telling them anything they didn’t already know.

But it was in the portraits where they found themselves and they were surprised because they saw themselves reflected in the images. And it was an incredible moment, they spent hours looking at them, exclaiming “look, that’s the aunt of so-and-so, or the friend of such-and-such.” It’s a very small island, everybody knows each other in some way. And I found out many things, names of people I didn’t know, people I’d just bumped into along the journey that I’d never properly met. And there I found myself with real people. I think it was a fundamental part of it all.

The portraits of the island’s inhabitants was “fundamental” to the Tike’a exhibition.

B.P. Let’s talk about the title of the book; Tike’a. It’s a word from the Rapanui language: Why did you choose it and what does it mean?

J.A. When I started to think about a name for the exposition – which has the same name as the book – I decided it had to be a word in Rapanui, which is the language of Easter island. So I started to research words, but realised it also had to be a word that would be easy to pronounce on the continent. Tike’a really caught my attention because it describes exactly what I had been doing in regards to the Easter Island culture.

Tike’a means…to see, but with an intention to understand. There isn’t a literal translation, but it describes an attempt to understand the object being observed. And that was what I was doing with the Rapanui culture. It was totally foreign and strange, and I was getting close to it to see it, to know it, to analyse it. It’s a word that summarised what I was doing, and I think this also echoed in the society.

Alderete’s work is strongly influenced by pop culture, vinyl covers, posters and contemporary culture.

B.P. Were you afraid of carrying out this observation, this Tike’a, from a prejudiced Western or colonial point of view?

J.A. In reality, all of my initial research was carried out through colonial or Western texts. Unfortunately it is only very recently that texts are beginning to be published by Rapanui authors, who can tell their stories from their own point of view, something that was unthinkable in the past. It was Westerners who felt this need to put the Rapanui culture into a book, and I suppose the same thing happened to me.

But I was always very aware of this, and questioned all of it. It always interested me, not only about Easter Island but all of the islands in Oceania, how it was related by illustrators and artists who travelled on the boats that discovered the islands. They tried to represent it but their work was plagued with vices from the era, from their own societies. For example, if an illustrator wanted to publish his work in a renowned Parisian magazine, they couldn’t put naked people in it – they had to invent clothes, even though they never existed in reality, and that was how we first encountered the culture. Not to mention some of the representations which were literally inventions, prefabricated before they even arrived on the islands.

All my work to understand the culture was linked to this and is aware of the fact that in my profession we can represent reality but we can also distort it to incredible levels.

The artist Dr Aldrete with his latest work. Photo by Frances Jenner

B.P. After the exhibition and the publication of Tike’a, would you say you’ve drawn a line under your obsession with Easter Island?

J.A. I hope so! This obsession has lasted at least 10 years, and my wife is afraid that at some point she’s going to come home and find me building a raft for whatever Tiki has arrived from Polynesia. When I went to the island the first time, I said to myself that this would be the end of my Easter Island obsession. The next year, I went back with the exhibition and I said to myself, right, this is the end of the obsession. Then there was the exposition in Mexico City, and I said–right–this time it’s definitely the end. But then the book came about…so let’s say I’ve been ending it in stages. Maybe it’s an important step to publish this book, to have compiled all the material from these last years of obsession, but I can’t guarantee that it’s over.

Tike’a: Rapanui and the Islands of the South Pacific (pp225) is in both English and Spanish and published by Rey Naranjo Editores.

Whether the obsession is over or not, the final version of the book is currently available to buy from Alderete’s online store for $23.