Buenos Aires, Argentina — President Javier Milei has singled out a new principal enemy ahead of Argentina’s October midterm elections: the media.

The libertarian politician has shifted focus from battling the deficit and fighting opposition figures — the “caste,” as he calls them — to waging war against the mainstream press.

Milei and much of his cabinet are now targeting journalists under the slogan, “People don’t hate journalists enough.” The campaign comes at a time when at least three journalists have recently experienced physical violence or public threats.

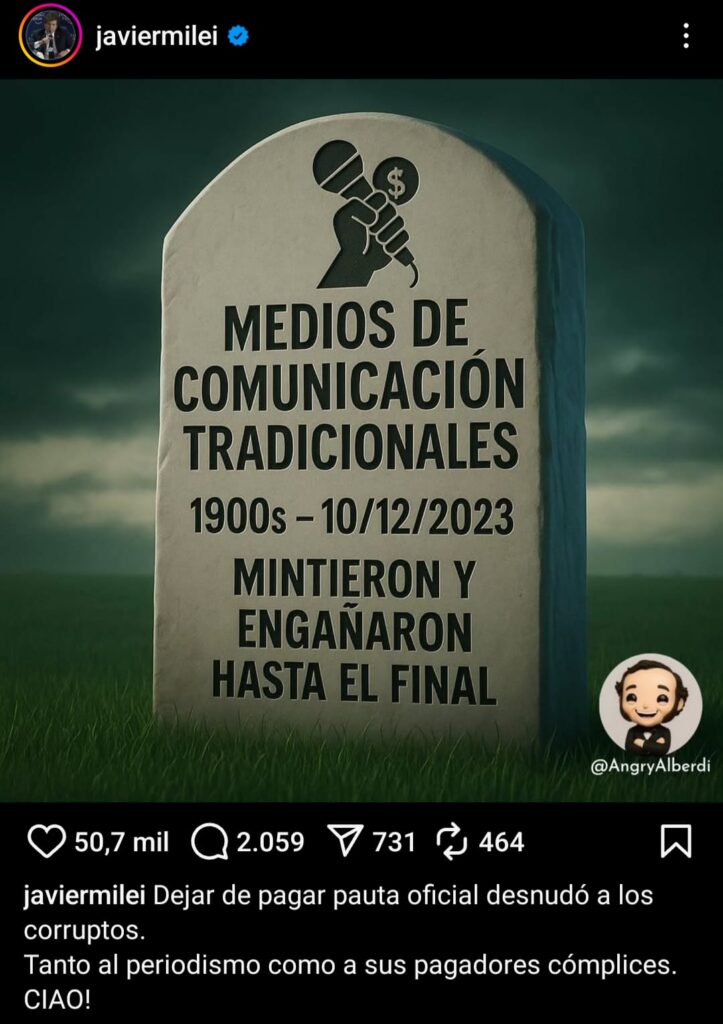

Over the past few weeks, President Milei has devoted much of his prolific social media activity — often consisting of dozens of posts and reposts each day — to attacking Argentine journalists. “Many journalists are extremely nitpicky when it comes to pointing out others’ mistakes. Are they ready to have the same standard applied to them? Can we show every time they lie, slander, and insult? That is, if they don’t lie — great. If they do, they’ll be exposed,” Milei wrote in a post on X.

In another widely shared post on April 30, Milei posted an image of himself as Morpheus from the 1999 film The Matrix, holding both a red and a blue pill, with the caption: “Time to choose.” The metaphor appeared to suggest that Milei sees himself as keeper of the “truth” represented by the red pill, while the mainstream media embodies the blue pill; remaining unaware, asleep or inside the Matrix.

Members of Milei’s cabinet have echoed his sentiments. Economy Minister Luis Caputo, for instance, claimed that journalism “is a profession that tends to disappear.”

On top of the online aggression, episodes of physical violence against journalists have become increasingly frequent in recent months. On March 12, photographer Pablo Grillo was covering a pensioners’ march near Congress and the subsequent government crackdown when he was struck in the forehead by a tear gas canister. The 35-year-old was in intensive care for more than a month. The government denied any wrongdoing by security forces, a claim that was quickly debunked by fellow journalists.

Roberto Navarro, founder of the news outlet El Destape, said he was attacked on April 21 by a group of unidentified individuals who insulted him while he was attending a meeting in a hotel lobby in Buenos Aires. The journalist was hospitalized after the incident and attributed the aggression to Milei’s public rhetoric. “I hold the president responsible for what happened to me and for what could happen in the future,” Navarro said in an editorial published days after the attack.

Days later, on April 29, a photographer was harassed by Santiago Caputo, a close aide to the president who is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in his cabinet despite holding no formal position. Caputo was attending a debate between Buenos Aires City legislative candidates when he confronted photographer Antonio Becerra, took his press credential, and photographed it with his phone. The act was widely perceived as a threat to Becerra’s work, particularly given the current political climate and Caputo’s reported influence over institutions such as Argentina’s intelligence services.

For Becerra, the incident “is another stone in what is unfortunately already commonplace, which is the great intimidation of the press.”

“They are pushing that narrative, ‘all journalists are corrupt, they are the cancer of the Republic.’ Well, it’s normal then that journalists are attacked on the street, which is extremely serious. Security forces beat us up during protests; we have to go to a march with riot gear just to cover a retirees’ demonstration at Congress. That’s the life we live,” the photographer told Argentina Reports.

Read more: Milei’s government cracks down on pensioner protests; brawl breaks out in Argentina’s Congress

“What we as journalists must do is not stop condemning this state policy and keep reporting. Ultimately, it’s part of a daily attack by the government on the press. And sadly, it’s nothing unusual,” Becerra concluded.

Milei and the press, a complicated relationship

Before becoming president, Milei maintained a less confrontational relationship with Argentine media. In fact, he built most of his political career on his constant appearances as a showman-economist on talk radio and television programs, starting in 2015.

By the early 2020s, the libertarian became a permanent guest on a number of shows on America TV, a public channel owned in part by Eduardo Eurnekian, his former employer in Corporación América. Milei leveraged that spotlight first for a seat in Congress and later to reach the Casa Rosada.

During the final stages of the presidential campaign, the libertarian candidate began clashing with media conglomerates, which he claimed were attempting to undermine his candidacy. He frequently complained about seemingly minor issues, such as people coughing on set, which he described as deliberate acts of sabotage.

After assuming the presidency, Milei significantly reduced his media appearances, granting interviews almost exclusively from the Casa Rosada under tightly controlled conditions. These included strict oversight of lighting (he has said he is photophobic) and even editing of the final material.

His efforts to manage his image became evident in February, when the news network Todo Noticias accidentally published a clip from an interview in which Milei was discussing a cryptocurrency scandal he is implicated in, known as LibraGate. The footage showed advisor Santiago Caputo stepping in mid-interview to prevent Milei from further implicating himself in the case.

Read more: Javier Milei pushes aggressive agenda in Argentina, hopes to move past $300 million crypto scandal

In March, Milei clashed with Grupo Clarín, Argentina’s major media conglomerate, after their telecommunications company, Telecom, purchased former competitor Telefonica. The president vowed to retract the billion-dollar operation “to defend the people of Argentina” and argued that media companies “pressure and manipulate governments to obtain benefits.”

“Let’s not tolerate intolerance”

The Argentine Journalism Forum (FOPEA) recently warned about “the escalation of attacks on journalists promoted by the country’s highest authority.”

“While tensions between rulers and the press are normal in a democratic system, attacks on the media often have direct effects on the full exercise of other civil and social rights. Not for nothing has the United Nations repeatedly stated that governments’ tolerance of unfavorable opinions and critical voices is a good indicator of their respect for human rights in general,” FOPEA argued in a press release.

“Beyond being intimidating, these words from the president represent a setback in democratic construction. In its 2024 Freedom of Expression Monitoring report, FOPEA recorded a 53% increase in attacks on the press compared to 2023. The report specifies that 44% of aggressors resorted to digital violence, which amplifies its impact. It is evident, then, that threats on social media against journalists are a natural consequence of the attacks on the press from the government,” FOPEA concluded.